Supported by the Digital Methods Initiative (DMI), Lakmusz and other invited partners have conducted a two-month-long social media research to identify the main actors driving attention to information about the Russian-Ukrainian war in six Eastern European languages. The research captured public posts and conversations from groups that were published on Facebook during the first year that followed the invasion of Ukraine (from 24 February 2022 to 10 January 2023). Since most of the disinformation agents support their claims with links to external sources, the study was limited to posts with external links that were used to identify problematic online spaces. In this article, we present results from the Hungarian media landscape. (The full report with the cross-country analysis will also be published soon).

Social media has increasingly become a preferred pathway to news, and war coverage of the Russia-Ukrainian war is almost live-streamed on online platforms. (The armed conflict has even earned itself the title, The First TikTok War). While tech platforms allow for instant commentary and coverage, it has also become a perplexing task for users to discern reliable information. On social media, established media producers compete with a number of newcomers for attention: foreign and security policy experts, military Telegram channels, amateur podcasters, and a growing number of foreign media products that since last February have entered news feeds with the aim to shape public opinion.

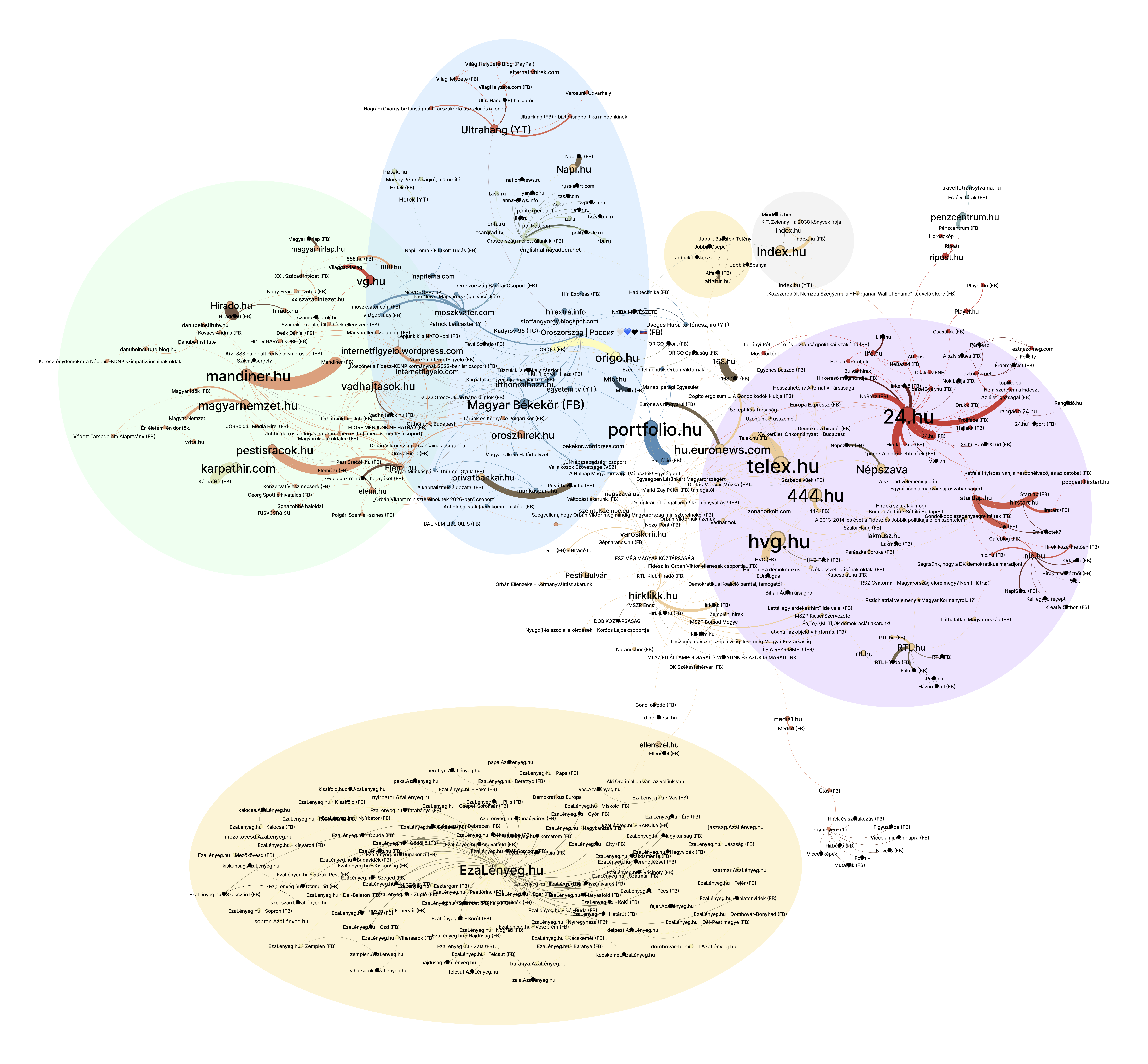

Hungary’s public sphere has long been consolidated around pro- and anti-government attitudes, and this political polarisation seemed to prevail also in the wake of the war. By mapping the most vocal actors on the topic of the war on Facebook, we once again found evidence of this partisan division but also discovered opposition echo chambers and entanglements among pro-government and pro-Russian accounts.

Our findings conclude that

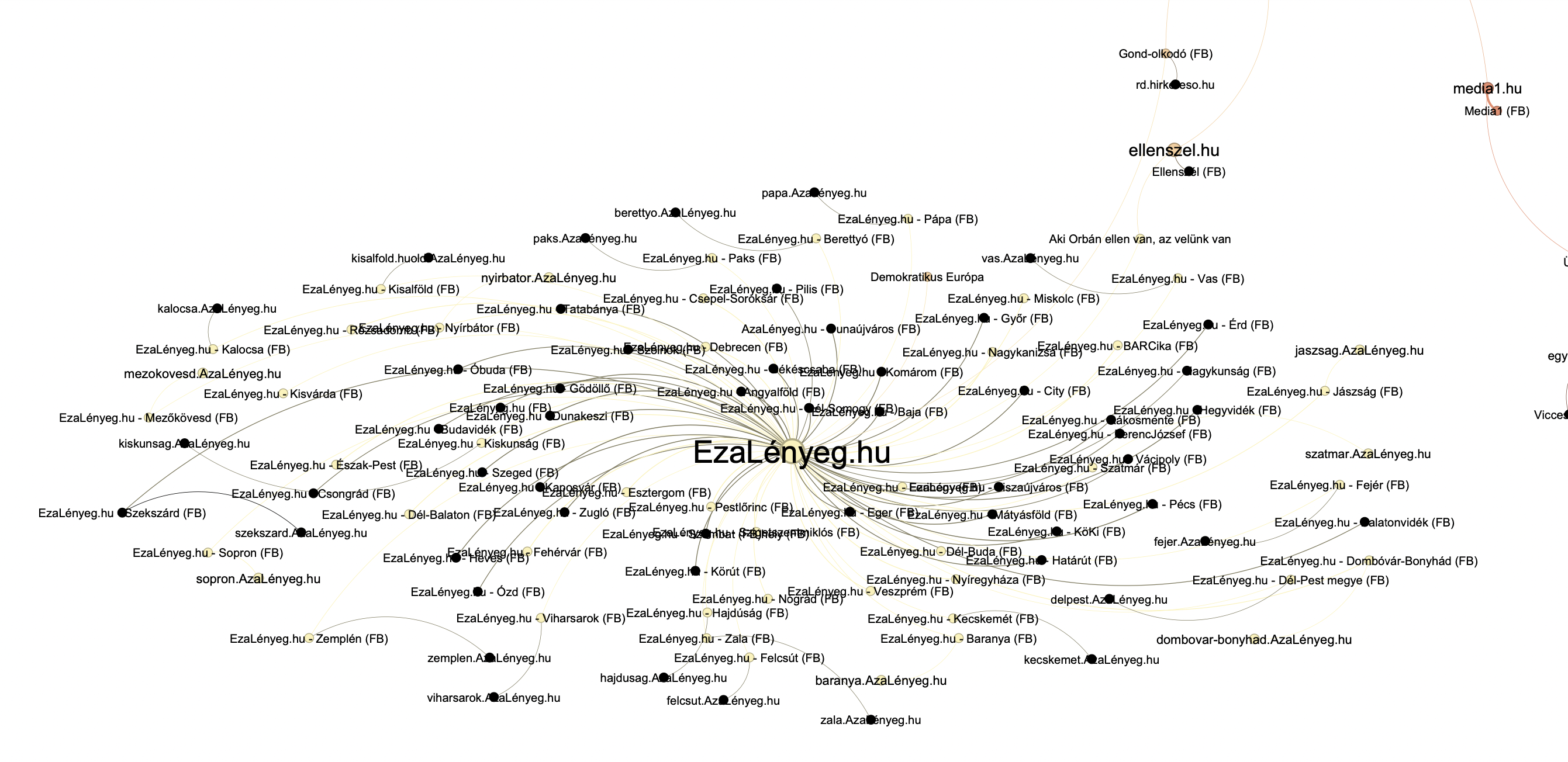

Zoom in on the network here.

The present research applied hyperlink analysis to assess what type of war-related content was disseminated on Facebook in Hungarian language and by whom. The prominent channels and their relational positions are visualized on a network map that also shows the partisanship of attention.

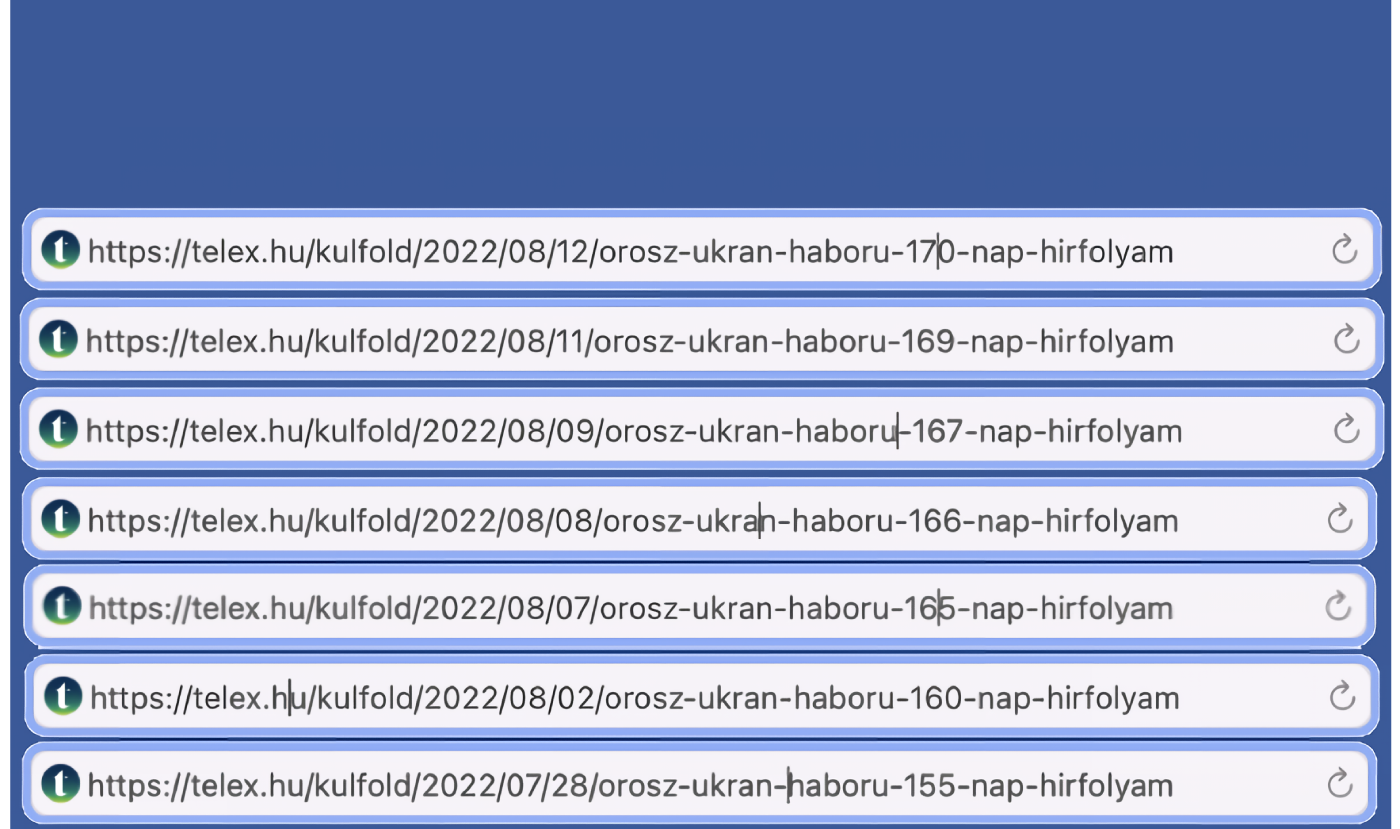

First, we created a corpus of pro-Russian and neutral keywords, that we later queried with Meta’s Crowdtangle tool. We have captured posts and conversations from Facebook pages, public groups, and verified accounts between 24.02.2022 - 10.01.2023. In the next step, we kept only posts with external links (for example, when an article from an external website was shared on Facebook). In total, 38 433 such links were identified, posted by 4597 unique actors. Then, we plotted the actors' network in Gephi and detected communities by running modularity algorithms. The next steps involved labeling those clusters by looking at the biggest or the most centric nodes. Using graph theory, we were able to make conclusions about particular media landscapes, as well as detect post-truth spaces within some of them.

The nodes or circles represent news sources. The size of each node indicates its relative importance in the network. The more links cite a news site (e.g. 24.hu), the larger the size of its node.

The edges, or links between the nodes, create the network's architecture. They represent the relationships among the nodes. The weight of the links is determined by the number of hyperlinks between Facebook accounts and each media source. For example, if someone shares something from Magyar Nemzet and from Russian News, that is an indication that Magyar Nemzet and Russian News draw a common set of readers. The greater the number of accounts that share links to the two sites, the closer the sites are on the map.

Background colors on the map indicate different clusters or groups. The actors within a group are densely connected to one another, while they have fewer external links to other actors outside of their group.

In the Hungarian language, war-related discourse on Facebook is maintained by ca. 4500 actors that form four big and several smaller clusters. These are the following:

1. Independent news media, pro-opposition, and openly anti-government groups

One dominant group is built around mainstream independent media outlets – 24.hu (2120 links), Telex (948), HVG (813), RTL (457), and 444.hu (444). War coverage by these online news portals is primarily injected into the system by their official Facebook pages, however, a plethora of opposition and anti-government groups also take part in the distribution of their articles (Demokráciát! Jogállamot! Kormányváltást!; Egységben Létünkért Magyarországért; Szabadelvűek, Szégyellem, hogy Orbán Viktor még mindig Magyarország miniszterelnöke).

Fact-checking units and outlets that were clearly established as a reaction to post-truth spaces are also part of this cluster (Ellenőrző by Telex and Lakmusz).

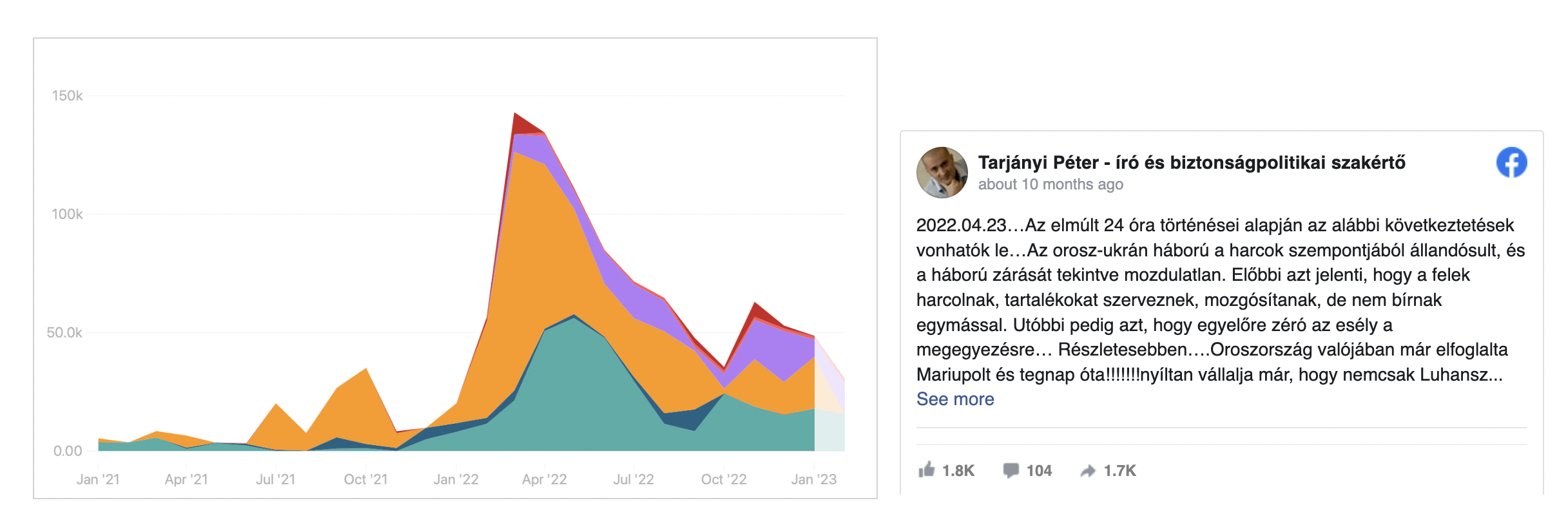

The former cop-turned-security analyst, Péter Tarjányi represents the experts within this hub. Tarjányi amassed a significant following on Facebook (237k) and hosts two solo shows (one on Index and another on Spirit FM) dedicated to war-related issues.

The interest in Tarjányi'a Facebook page grew significantly in January 2022, then it fell in the course of the summer. Source: CrowdTangle.

2. Hyperpartisian news sites

(EzALényeg.hu published by Orakulum 2020 Ltd. and Alfahír, the party newspaper of Jobbik)

On the non-governmental pole of the network, but sharply separated from the independent news cluster is a large community defined exclusively by one hyper-partisan site and its local mutations, EzALényeg.hu. The medium, owned by the Hungarian company, Orakulum 2020 Ltd. has made a name for itself with its digital ad spending and innovative micro-targeting that was first tried and tested in the 2019 municipal elections. The portal publishes flashy news with clickbait headlines that variously call Putin ‘a war-criminal Russian dictator’ and ‘Viktor Orbán’s master’. The articles’ arguments tend to reduce complex issues to simplistic answers (that either blame Orbán or Putin).

The main site and the various EzALényeg subpages form a network within a network that has just a few external connections. Due to this factor, this exemplifies what we defined as a “post-truth” space which, in this special case, takes up the form of an echo chamber.

3-4. Pro-government, pro-Russian, and far-right sources

On the other side of the map, there is a clear overlap between pro-government, far-right, and pro-Russian journalism sites and blogs. Part of them are established pro-government media outlets: Mandiner (892 references), Pesti Srácok (581), Origo (520), and Magyar Nemzet (331) are all controlled by the Central European Press and Media Foundation. These sites, however, receive inlinks from the same groups that reference pro-Russian and fringe far-right websites such as Vadhajtások, Elemi. hu, Nemzeti Internet Figyelő, and Orosz Hírek, accounting for the proximity and partial overlap between the two clusters. These sites are edited by anonymous actors and do not necessarily follow professional journalistic norms. The fact that pro-government legacy media and these obscure sources attract the same readership can be explained by the similarity of the content they share.

The central position within the pro-Russian cluster is occupied by the Facebook page of Magyar Békekör [The Community for Peace of Hungary]. The initiative was spearheaded in 2014 by Endre Simó to conduct civil diplomacy and step up against NATO setting foot in the country. The peace mission’s page was referenced 270 times across the network from political parties (Hungarian Workers’ Party) to communities interested in the situation of the Hungarian border with Ukraine.

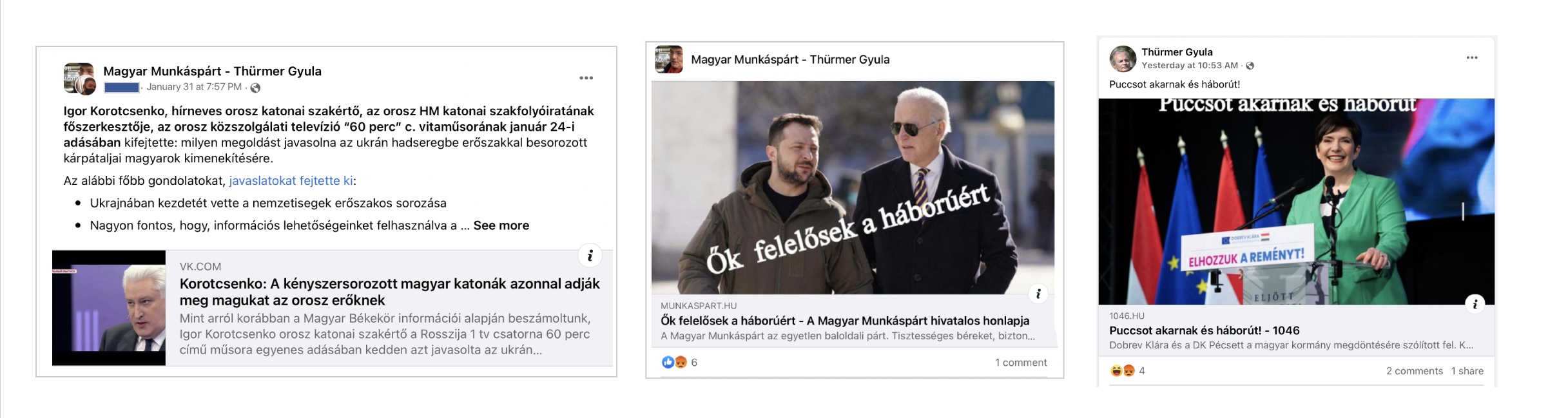

Gyula Thürmer and the Workers’ Party are the only representatives of institutional politics in the pro-Russian cluster. Until recently, the party has organized several peace protests together with the above-mentioned civil organization. In their public appearances and communications, the party recurrently points to the Ukrainian president, who in their interpretation, poses a physical threat to the Hungarian minority living in Ukraine. (They regularly mention ethnically targeted forced conscription, an allegation that has been refuted several times due to missing evidence). Also, the party still echoes the slogan used by Fidesz in the 2022 election campaign, claiming that ‘the opposition drags Hungary into war'.

Next to content creators, we find a bunch of unknown Facebook accounts that deem the above sources worthy of citation: they are spreaders that share links into small groups and communities formed around a specialized interest or political alignment. These groups either amass people who openly stand up for Russia (Friends of Russia, Russia | Россия 🤍💙❤️ 🇷🇺, NOVOROSSIJA), support revisionism (Let Carpathia be Hungarian land again; Let's fly the Székely flag!) or are simply fans of military gadgets (Military Technology).

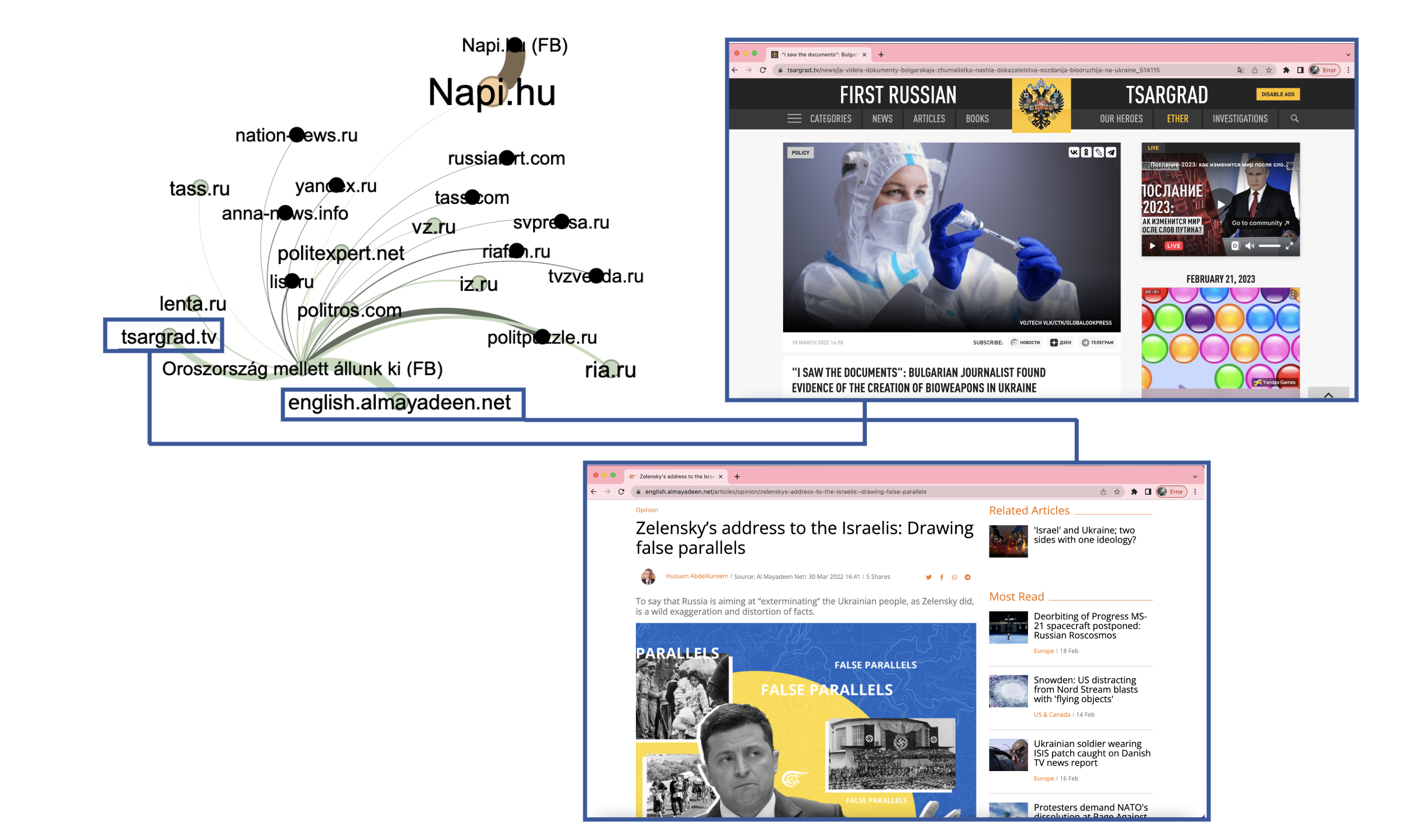

Among the groups, one stands out with its peculiar linking and content-sharing behavior (We stand up for Russia) that relies mostly on Russian and Arabic sources (such as the state-run TASS and RIA Novosti news agencies, Tsargrad TV, Russia Today, and the English Al Mayadeen). The latter media outlet is a pan-Arabist satellite news channel with a pro-Hezbollah and pro-Syrian government stance. The portal has been reporting on Zelenskyy’s 'Ukrainian Nazi leadership' since the outbreak of the war and has also circulated the theory of bioweapons.