Others have recently been tempted to copy the Russian Foreign Agents Act

2024. augusztus 27. 10:20

Ezt a cikket 2024

augusztusában írtuk.

A benne lévő

információk azóta elavulhattak.

What is called ‘sovereignty protection’ in Hungary is not an unfamiliar concept in the wider region: in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Turkey, the fight against ‘foreign-funded organizations’ is also being waged, making it impossible for the civil sector and journalists to operate. Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán’s friends and allies, Robert Fico, the prime minister of Slovakia and Milorad Dodik, President of Republika Srpska are already planning similar laws.

Last December, the Hungarian parliament passed a law called the Sovereignty Protection Act, similar in spirit to the Russian Foreign Agents Act.

Although Hungarian government politicians initially denied that the so-called ‘sovereignty protection’ law was part of a campaign against civil society and the independent press, it is now clear in practice who and how the Sovereignty Protection Office set up by the law is targeting.

For example:

- At the end of June, a comprehensive investigation was launched against the investigative newsroom Átlátszó and the anti-corruption organization Transparency International Hungary;

- The office published ‘studies’ of dubious methodology that listed ‘ pro-war ’ newspapers and articles spreading ‘ disinformation ’;

- And public bodies were approached by the Sovereignty Protection Office to collect information for them continously on a ‘sovereignty protection basis’, including bank account details of certain individuals.

In recent months, similar regulations and proposals have been put on the agenda in other countries in the wider region:

- Foreign agent laws have recently been adopted in Georgia and Kyrgyzstan,

- Bills have been proposed in the Republika Srpska, Slovakia and Turkey,

- Legislation against foreign influence was proposed in North Macedonia and Serbia.

Note: We were able to mark Bosnia and Herzegovina on the map, but the legislation only applies to one entity in the country, Republika Srpska.

In this article, we show what regulations are in force, or what laws are planned in these countries, who these laws apply to and how they work.

In conclusion, the common feature of the foreign agent laws adopted, submitted or proposed in the region is that, although the submitters claim that they are modelled on a certain US law, their content is more similar to the Russian foreign agent law. And, according to the stakeholders we interviewed, these laws are capable of suppressing critical voices, pro-democracy NGOs and the independent press.

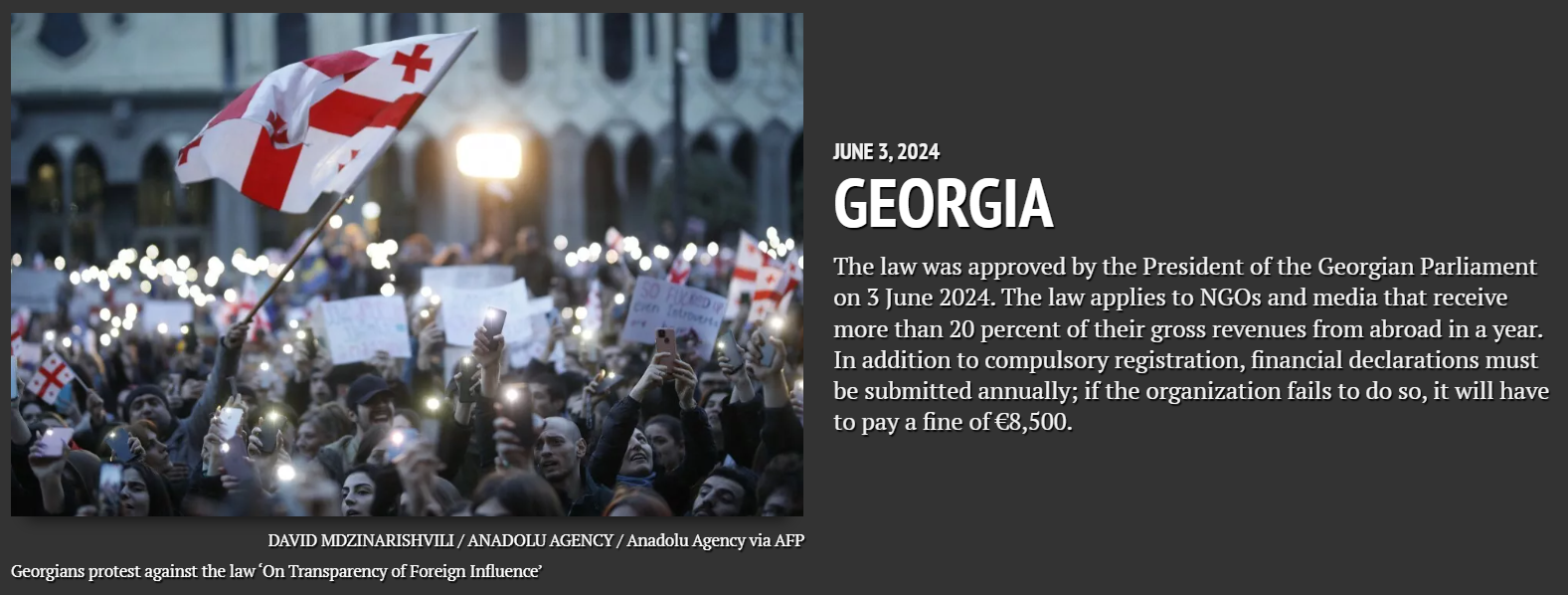

Where the laws are already adopted: Georgia, Kyrgyzstan

‘According to the government’s justification, this legislation is a transparency measure, also known as the Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence . But it really has nothing to do with transparency’ Tamar Kintsurashvili , director of the Georgian Media Development Foundation and editor-in-chief of the fact-checking site Myth Detector , commented to Lakmusz in late June.

The Georgian Dream – Democratic Georgia party, which has been in power in the country since 2012, cited the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) as a model to follow when introducing the Georgian law. However, the two laws are not similar, the Georgian legislation is much more like the Russian model. International lawyer Ted Jonas, who has lived in Georgia for decades, has written at length about the differences between the US and Georgian laws, and has found, among other things, that:

- US law defines a foreign agent as a person (legal or physical) who is controlled by or acts under the direction of a foreign power and acts in the interest of that foreign power, whereas Georgian law defines a foreign agent as an entity that receives more than 20 percent of its funding from a ‘foreign power’;

- US law does not presume that a foreign-supported organization is a foreign agent, but Georgian law presumes that the mere fact that an organization receives foreign support is sufficient to be labelled a foreign agent.

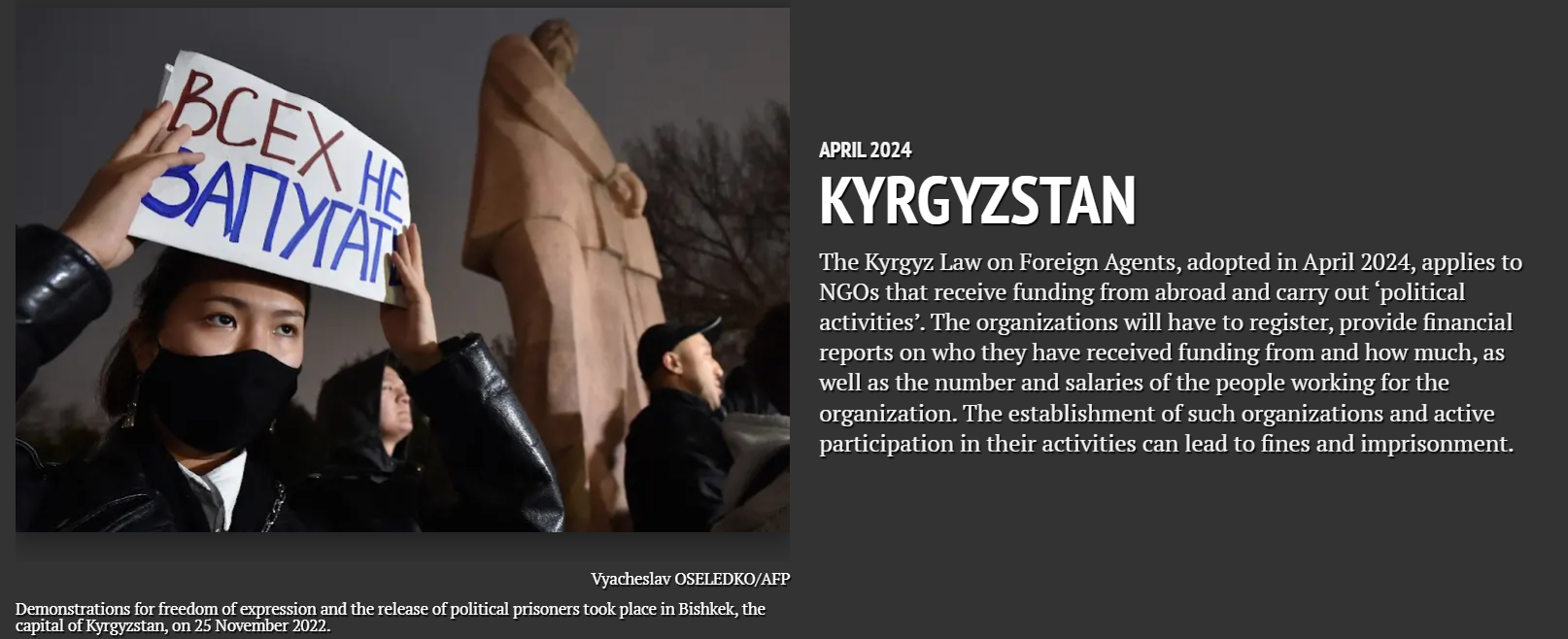

‘The suppression of critical voices did not start with the adoption of the Russian Foreign Agents Law in Kyrgyzstan. The best period in terms of freedoms was between 2010 and 2016, but with the current president Sadyr Japarov coming to power, the situation has got worse and worse, which has been exacerbated by the Russian-Ukrainian war,’

said Kyrgyz journalist Bektour Iskender, who left Kyrgyzstan in 2021 due to repressive measures, in response to a question from Lakmusz.

The Kyrgyz leadership, in power since 2020, has good relations with Russia , and their foreign agent law is modelled on the Russian Foreign Agents Law and applies to organizations that engage in political activity. However, the law defines political activity very broadly.

‘Under the law, a great many actions can be considered political. This understandably frightens many people. The first targets are independent media and NGOs that monitor elections, for example. One NGO has already ceased its activities and two news outlets have left the country and are working in exile,’

said Bektour.

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) warned that the Kyrgyz law is stigmatizing, it can easily be abused and that the definition of ‘political activity’ is extremely vague.

Where foreign agents laws are planned: Republika Srpska, Slovakia, Turkey

‘The proposed law is stricter than the one recently adopted in Georgia, because while there 20 percent of funding must come from abroad to be classified as a foreign agent, there is no such limit in the Republika Srpska,’ Enes Hodžić , an investigative journalist from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) in Bosnia, told Lakmusz. Although Enes does not live on the territory of the Republika Srpska and BIRN is based in Sarajevo, he would be affected by the foreign agent law: since he works for a foreign-funded organization, he would be treated as a foreign agent if he travels to the Republic of Serbia to work, which he does quite often.

The law, at least in its latest (May) version , would not only apply to organizations registered in the Republika Srpska, but would also monitor NGOs throughout the whole of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

During the preparation of the law, the President of the Republika Srpska, the famously pro-Russian Milorad Dodik, said that the law was modelled on the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) . The US embassy in Bosnia distanced itself from Dodik’s remark in a statement , saying that the US model is in stark contrast to the approach Dodik outlined.

In the press release, the US embassy said that

‘FARA does not prohibit or restrict any activity and does not apply to independent media or NGOs .’

Back in March last year, Radio Free Europe Bosnia looked at the similarities between the law proposed in the Republika Srpska and the Russian Foreign Agents Law, and found many similarities.

The narrative is very similar in Hungary’s northern neighbour: in Slovakia, the far-right and pro-Russian Slovak National Party (SNS), currently part of the governing coalition, proposed a similar law in April, targeting mainly NGOs working on disinformation, human rights or political accountability.

Although the political leadership adduce the US Foreign Agents Registration Act as a model to follow, the Slovak law is also modelled on the Russian Foreign Agents Law, in line with other countries in the region. According to Slovak civilians, another point of reference for the Slovak ‘foreign agents law’ could be ‘the Transparency Law’ adopted in Hungary in 2017. However, the Slovak version of the law can even be stricter because it would give stronger powers to the Ministry of Interior.

The proposal is still under discussion and negotiation. If the law is presented and adopted, it could enter into force on 1 January 2025.

In May this year, Turkey also hinted at tightening up its already tough rules: the pro-government daily Yeni Safak leaked that the Turkish government would amend the Penal Code to broaden the definition of the crime of espionage and introduce the concept of ‘foreign influence agent’ as a new criminal category. Critics say the legislation would be a further blow to Turkish democracy and independent journalism, with experts interpreting the move as an extension of the Disinformation Law adopted in October 2022 , which is officially justified as ‘combating fake news and disinformation’ but is in fact used by the Turkish authorities to stifle dissent and criticism.

According to a report by Free Web Turkey, the law was invoked by the authorities to restrict access to more than 40,000 URLs in 2022. News about Erdoğan and his family was blocked the most, followed by news about individuals and organizations close to the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Where laws have only been proposed for the time being: North Macedonia, Serbia

Although there is no ‘foreign agent law’ in force in North Macedonia, the openly pro-Russian Levica party has included in its electoral programme the banning and criminalization of fact-checking on social media and the ‘desorosization’ (referring to George Soros, Hungarian-American businessman who supports NGOs in the region) of the civil society in North Macedonia. According to the latter, sanctions would be imposed if a foreign-backed NGO spreads ‘political propaganda’ in North Macedonia. Moreover, it would be forbidden to support an NGO from abroad at all.

Aleksandar Vulin and Sergey Lavrov in Moscow, 22 August 2022. Photo: Serbian Internal Affairs Ministr / ANADOLU AGENCY / Anadolu via AFP

Serbia is moving in a similar direction: in May this year, the left-wing nationalist Movement of Socialists party announced that it was preparing a bill to restrict the activities of NGOs. It is unclear whether the party and its openly pro-Russian founder and former leader Aleksandar Vulin can gather enough support to make the bill a reality, but NGOs are already worried. According to Maja Stojanovic, head of Civic Initiatives, ‘Vulin and his party always say what the government thinks but not allowed to say.’

Committees against Russian influence: Albania, Poland

In addition to the above, parliamentary committees against disinformation and Russian-Belorussian influence have been set up in two countries, but it is not yet clear what they will be used for and how. From the information available so far, it seems that they have been set up to filter out Russian influence rather than to undermine civil society and NGOs.

The Albanian government announced the creation of the parliamentary commission on 1 April this year, while in Poland, Donald Tusk’s government revived a commission set up by the Law and Justice (PiS) government in 2023.

What does the European Union want and what can it do?

The European Union itself has drafted a proposal aimed at reducing foreign influence. However, critics refer to the package as the EU’s ‘foreign agents law’ and fear that ‘politicians like Viktor Orban could use it as a weapon to combat pro-democracy forces in their countries.’

Meanwhile, it is the EU institutions that would have the means to fight against foreign agent-type laws in EU member states and to put pressure on EU candidate countries.

When the Hungarian Parliament voted in favour of the NGO law in the summer of 2017, the European Commission issued infringement proceedings against Hungary within a week or two. And after the European Court of Justice ruled in summer 2020 that the Hungarian law was illegal, the Hungarian government was forced to withdraw it in April 2021.

In April 2024, the European Parliament also condemned the law, which the Hungarian government called ‘sovereignty protection act’, and the Commission launched a new infringement procedure in February , and in May it also announced that it would refer the case to the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Georgian protesters in Tbilisi, 17 April 2024. Photo: Davit Kachkachishvili / ANADOLU / Anadolu via AFP

The situation in Slovakia is similar: in July this year, the European Commission warned the Slovak government that if they adopted the Foreign Agents Act, they would also be subject to infringement proceedings. Alexandra Tóthová, executive director of the Slovak think tank Strategic Analysis , told Lakmusz that the EU will most likely take action against the Slovak legislation if it is adopted, as it is in its current form contradicts EU law on several points.

The European Commission has also previously issued resolutions condemning the foreign agent laws in Georgia , the Republika Srpska , and Kyrgyzstan , all of which are on the EU candidate list except Kyrgyzstan. And after the adoption of the Georgian law, the EU suspended the country’s EU accession process and postponed the allocation of €30 million to support the country’s defence sector.

Alexandra Tóthová, Bektour Iskender and Enes Hodžić contributed to this article.

Cover photo: Bence Kiss/444.hu

Translated by Benedek Totth

A szerzőről

Fülöp Zsófia

2023 májusától a Lakmusz újságírója, korábban 9 évig a Magyar Narancsnál dolgozott, főként egészségügyről, szociális ügyekről és marginalizált csoportokról írt. Az oxfordi Reuters Institute ösztöndíjasaként a romák médiareprezentációját kutatta.

Kövess minket!

Ne maradj le egy anyagunkról sem, kövess minket máshol is!

Ajánlott cikkeink

Fáklyaként lángolt egy dubaji luxushotel és az USA rijádi nagykövetsége? – a magyar médiába is beszivárogtak a közel-keleti konfliktusról terjedő hamis képek

Innovatív tényellenőrző formátumokat kidolgozó európai projektben vesz részt a Lakmusz